| Welcome To Our “The Philosophy & Rewards Of Survival” Section |

Kurt Saxon

about a quart of 90 proof alcohol for less than a dollar.

So I gathered up all the books I had concerning alcohol and

set out to master the process on a small scale. My Emporium of Arts and Sciences

of 1814 told of whisky production in Lancaster County, PA. In a year, from 611

stills, 3,295,500 gallons, or 5,394 gallons per still, or an average of 14.77

gallons per still per day was produced. Going by the low level of technology in

1814 the process had to be pretty simple. And it is.

Whiskey. In Lancaster county, Pennsylvania, during a year

ending with April 1814, six hundred and eleven stills, manufactured 3,295,500

gallons of whiskey.

But try finding that simple process in a modern book. Most of

the books on the subject are frauds. No beginner could learn how to make ethyl

alcohol from any of them.

Take “The Moonshiner’s Manual”, by a man calling

himself Michael Barleycorn, copyright 1975. The book is entertaining, cleverly

illustrated, but filled with misinformation and nonsense. I’ll criticize it, but

only to show you why you can’t depend on such books to live up to their claims.

When

When

you buy a book telling you how to do something illegal, to complain that it is

inaccurate is almost an admission that you’re up to no good. The publisher banks

on that. That’s why shady outfits like Delta, Paladin and Butokukai keep

cranking out garbage to sell to suckers. Books with sensational titles and

seductive ad copy, but with nothing of value between the covers.

Getting back to “The Moonshiner’s Manual”, it says

to put 25 pounds of cracked corn in a gunny sack and soak it in a tub of warm

water for three days! It suggests that natural fermentation will come into play.

What you would get in that three days would be 25 pounds of, not fermented, but

rotted corn. Then you are supposed to put the corn, sack and all, into the vat

with 30 pounds of pure cane sugar and 1-2 quarts of molasses.

In a later, scaled down recipe, he calls for 2 1/2 to 5

pounds of cracked corn, in a small sack, 5 to 10 pounds of sugar and 1 pint of

molasses or 1 cup of unflavored malt.

The corn, sack and all, is to be put into the fermenting vat.

Insane! The part about the gunny sack is an old technique for sprouting the

corn.

Sprouting, or malting, turns most of the starch into sugars

and diastase. The sugars are readily converted into alcohol by yeast and the

diastase acts on the remaining starch to turn it into dextrine, also quickly

acted on by the yeast.

The gunny sack is filled with whole, non-hybrid corn, not

cracked. The sack is immersed in a tub of warm water and left for 24 hours, then

drained. Then it is flooded with warm water once every 24 hours until it expands

and bursts. These are sprouts. Plenty of dextrine and diastase. No cane sugar is

needed. To throw the sack into the fermenting vat would be stupid.

The sprouted grain is then pulverized and put in the

fermenting vat. Water and yeast are added and the fermentation proceeds apace

Both recipes call for molasses, which is unnecessary.

It should be obvious that Michael wrote the book to sell to

suckers and had no real knowledge of moonshining.

He goes into great detail about the penalties attached to

moonshining. This has a purpose and is a paradox at the same time. First, he’s

scaring the average reader out of any notion of making his own booze. This keeps

most from trying the techniques, finding them useless and demanding refunds. The

paradox arises in the fact that no one could use these instructions for making

alcohol, thus, the warnings are unnecessary.

Another book, and a good one, is “Solargas”, by

David Hoye, 1979. This is about fuel. Hoye goes to great lengths to make sure

the smallest batch is poisoned by denatured alcohol, lest a sip pass the lip.

Only one page tells of making alcohol from ground, unsprouted

corn. All other references are to sprouted corn.

There are two bars to making booze by following this book.

The first is the constant harping on getting Federal permission and filling out

all those forms. This intimidates. The second is that you can no longer buy

non-hybrid corn at your local feed and seed store. It is all hybrid and only

about 10% will sprout, leaving 90% a rotten mess. You have to buy it from a

farmer who grows non-hybrid corn or grow it yourself.

I didn’t know this until I began researching. I meant to use

Hoye’s book to make alcohol and then tell you how. I processed two pounds of

corn and was surprised to see that only one out of ten grains sprouted. The rest

rotted. Rotted starch doesn’t convert to alcohol.

There are several alcohol for fuel books on the market. Most

of them are inaccurate and therefore fraudulent. Even the best were published

with doubtful sincerity. I’m sure their publishers realized that nine out of ten

buyers of the books had no intention of converting their vehicles to alcohol.

Consider; you can modify your vehicle’s engine to run on alcohol, propane,

methane, diesel etc. Then, when you’re on the road and run out of fuel you don’t

just turn into the nearest gas station, turn a knob on your engine and reconvert

to gasoline. No. If you convert, you’re stuck with it until you convert back.

Moreover, aside from all the forms and bureaucracy with the

Feds, converting, even for farm vehicles, isn’t cost-effective. And if you

intend to go commercial, you face a starting cost of maybe a hundred thousand

dollars, not to mention bucking the competition.

So, I repeat my contention that the average guy who buys a

book on making alcohol wants to save on his liquor bills. With what you are

going to learn here, you will never need to buy booze again, much less another

silly book on making it.

But before we go into that, let me explain the law. You can

distill alcohol if you pay the liquor tax on it. So if you don’t pay the liquor

tax, with all the red tape that involves, the bottom line is that you are guilty

of tax evasion.

Sure, they can jail you, take everything you have, put your

wife on the street, sell your kids. I’m not really kidding!

But so what? If you’re making your own, how can anyone know

what you do when you’re alone?

Even so, let’s say the Feds wanted to harass you. They have

to prosecute, in these days of overcrowded jails and backed-up court dockets.

Then they have to prove to a jury that your still was for making alcohol,

instead of for purifying water as is done in hundreds of thousands of homes,

with stills bought mainly from Sears.

Or maybe you admit you made the still but it’s a lab still

for ever so many uses, even for purifying water. Unless they catch you in the

act of distilling alcohol, how could they prove it to a jury?

Many people have asked me if it is advisable to carry a

concealed weapon. I ask them if they have ever been searched by the police. The

answer has always been no.

So I ask what makes a person think he will be searched after

he begins to carry a concealed weapon?

The same goes for distilling. Even so, I am not encouraging

you to break the stupid law. You shouldn’t even drink. But when this system

unravels a bit more, you will have a trade which will insure your survival. The

techniques I’ll show you in this and following articles will enable you to make

beer, wine, whiskey, etc. It’s easy.

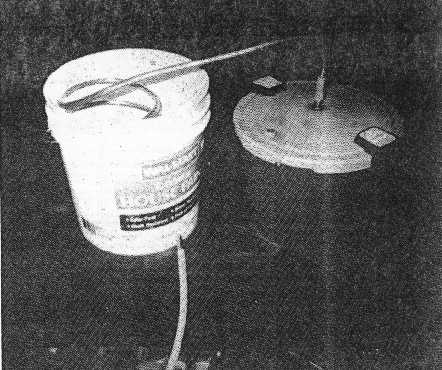

The equipment won’t be expensive, either. It can consist of a

food dryer like mine, a Corona grain mill and a pressure cooker (unless you have

a Kenmore water purifier from Sears). You will also need ten feet of 3/8 inch

copper tubing, bought at most hardware stores for 50 cents a foot. The rest is

just odds and ends you may have or can get at little cost.

I’m

I’m

not going to write everything in this article because I don’t have room and it

would be too much to absorb at this time. Instead, I’ll show you how to make the

still and how to run off a quart of very high-proof alcohol.

It would be best for you to get a Kenmore Water Purifier from

Sears. Otherwise, get a pressure cooker of at least one gallon capacity. That’s

the pot for the still. Mine is a teflon-coated Presto Chicken Fryer of a one

gallon capacity. I don’t know how much it cost new as I got it for a couple of

dollars a a garage sale. You may have to get one new but make sure it’s coated

as alcohol reacts with aluminum.

You need a pressure cooker. Otherwise the alcohol will go out

into the air if you just use any old cook pot, no matter how close-fitting the

lid. Also, it takes a little pressure to force the fumes through, especially if

the coil isn’t completely slanted and pressure is needed to push the liquid

alcohol through.

Next get 10 feet of copper tubing. Copper is better than

plastic or rubber. It causes no bad taste. Also, it gives up heat into the cool

water better than plastic or rubber and will last a lifetime.

Next

Next

get a two gallon plastic paint bucket or similar. Drill a 3/8 inch hole near the

bottom of the bucket.

Now for bending the coil. You do it an inch at a time and it

is pretty tedious. It takes a few minutes to get the hang of it but then you’ll

be moving right along.

First, bend one end downward to connect with the pressure

cooker vent. You’ll not get the copper tubing over the vent so you will need

about two inches of 3/8 inch latex tubing, bought at any pharmacy for about 60

cents a foot.

When you have the downward bend done, without crimping it, go

over about 14 inches and start on the coil itself.

Keep bending so you have circles about six inches across. It

shouldn’t crimp if you bend it gently an inch at a time. But if it does start to

crimp, just use a pair of pliers on each side of the crimp to pressure it back.

When you have five or six circles, shove the end through the

hole in the bucket. Next use some GOOP to seal it inside and out. GOOP can be

bought at any good hardware store. It is a plastic sealant, quite thick and

takes a couple of hours to set and about 24 hours to really harden.

the bucket, squeeze a large dollop on a pencil and stick it down to the tubing

in the hole. Work it around and under and it will sag evenly and flow around the

tube and rest on the bottom of the bucket.

Then take the tube of GOOP and squeeze some around the

outside tubing. After a few minutes it will sag and, with the pencil, pull up

the sag and place it back around the tube and it will begin to harden. A day

later it will be hard and your condenser will be water-tight forever.

If the end of the tube protrudes only a couple of inches from

the condenser and that’s not enough to reach over the stove to flow into the

container, you can attach a few inches of latex tubing to it so it will be long

enough.

Now you want to find the proper temperature for distilling.

Put a gallon of water in the pot and set it to boiling. Then turn down the heat

to a rolling boil and mark the setting on the stove or hot plate so you can just

set it in place from then on.

Alcohol boils at 173 degrees F and water boils at 212. The

rolling boil is slightly lower but much hotter than needed to vaporize alcohol.

But that’s alright. So some water will come over. But the alcohol will flow with

the higher temperature. When the alcohol is out the flow will stop and be

replaced by a trickle which will be water and the distilling will be finished.

To test the system, and so you can do something right away,

buy a gallon of cheap wine with an alcohol content of 10-13%. When I was a bum I

would pour a gallon of $3.00 Burgundy into my still and put a quart jar under

the spout. When the flow of alcohol turned to a trickle of water, sure enough, I

would have a quart of about 90 proof alcohol. It added up to at least $11.00

worth of hard liquor for only $3.00.

I would cut that with juice or whatever and have enough to

party with my friends or have several glorious drunks. You can’t get that

crocked on 13% volume wine.

If you have made your own still, you need to cool the

condenser so the alcohol will liquefy. If you are using a hot plate to heat the

pot, you can situate the still by the sink. With another hole drilled near the

bottom of the bucket and another tube coming from the cold faucet, the warm

water would be constantly replaced by cold as the water left the bucket by

another tube into the sink.

But

But

that is an awful waste of water and would show up on your utility bill. You

could use ice cubes, which is quite a job. My way was to freeze cans of water. I

would put several average cans of ice in the bucket and fill it with water. As

they melted I would just transfer a can of water back to the freezing

compartment of my fridge and replace it with another ice can.

If you have a setup by a stream, you would have a faucet at

the bottom of the condenser. With the faucet open you would replace the warm

water with buckets of cold from the stream.

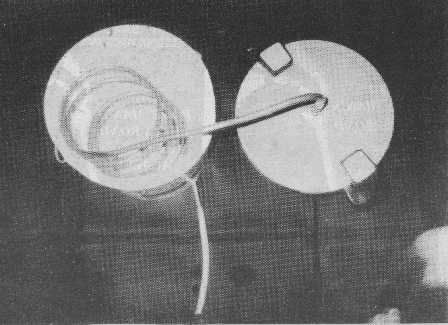

Now to the making of basic moonshine. For this you will need

at least one cat-litter container. These are the perfect size for a batch of

mash. They are sold in every supermarket for about $5.00. If you have cats, you

may already have some or may get them from friends. Barring that, it is worth

the price for the container.

These containers hold about 2 1/2 gallons. A batch of mash is

1 gallon and 3 quarts, so there is plenty of room. You can also watch what’s

happening.

First you drill a quarter-inch hole in the cap and push a

half-inch of two feet of quarter-inch plastic tubing through and GOOP it on both

sides. This is an ingenious way of knowing when the yeast has stopped working

and the alcohol content is as high as it is going to go. You put the end of the

tube into a jar of water and the carbon dioxide from the working yeast comes up

through the water in the jar. When the bubbles stop coming, or slow to a burp

every two minuets, it is ready. This also keeps your working mash odor-free.

Next, you finely grind two pounds of corn, sprouted to about

a half inch, in your Corona grain mill. Then get a cook pot holding over two

gallons. They are relatively cheap at Wal-Mart and can be gotten for a couple of

dollars from most second-hand stores. Avoid aluminum. Use stainless steel or

enamel.

Pour in two gallons of hot tap water and then bring it to a

brisk boil. Then dribble in the ground corn meal, stirring all the while so it

doesn’t lump.

Cooking the mash serves two purposes. First, it breaks down

the starch granules so the yeast can more effectively work on them. Second, it

kills any bacteria which might otherwise spoil the mash.

After thirty or forty minutes, take the pot off the heat and

put it in a dishpan of cold water to cool it down. It shouldn’t have any lumps

in it since that would cause uneven fermentation. If you have stirred it

properly, there should not be any lumps. In case there are, break them up with

any hand mixer.

Now for the yeast-sugar mix. Weigh out 1/2 pound of sugar and

put it in a measuring pitcher. Then add hot water until it reaches the quart

mark. The sugar should cool it to a temperature safe for the yeast. If it feels

warm but not hot, dump a package of active dry yeast (not fast-rising or acting

yeast) into the sugar and warm water. Stir it with a fork until it dissolves.

Then put a plate over the pitcher and let it alone for about an hour. It will be

covered with froth. Stir it again and then look to the mash.

Pour the mash into the cat-litter container. For this you

will need a funnel, lest it slop. The best funnel is one bought at any

auto-supply department and is used for putting transmission fluid in your

engine. Cut the funnel off nine inches from the top. This will allow 1 1/2

inches down inside the container and 1 1/2 inches across to let the mash flow

smoothly.

If

If

the mash is warm but no longer hot, pour in the yeast and sugar and give the

container a few sloshes. But don’t try to get it totally mixed. If it should be

mixed too much, it might rise up and clog the tube. This would cause pressure

and blow the lid off and mash would be all over the place.

If you don’t use the cat-litter container, measure the one

you use for at least 2 1/2 gallons. Never fill it with the mixture past the 2

gallon mark.

Now, put the container in the warmest part of your home, but

not over 85 or 90 degrees. The warmer it is within the safe limits, the faster

it will work.

With the cap on firmly and the tube in the jar, the bubbles

should appear in an hour or so. After a few days, they will slow down and

finally stop, at least except for a burp every couple of minuets.

Now you are ready to distill. It is too much trouble to

separate the liquid from the mash. The cooked mash isn’t too inclined to stick.

But it is a good idea to add water to completely fill the container when it is

ready to distill and then to shake it well before pouring some into the still.

Thus diluted the mash is pretty much in suspension so it won’t stick or burn.

Fill the pot only two-thirds full and keep the heat at Medium.

When it heats up, the alcohol will come over in a fairly fast

trickle. When the alcohol is all out you’ll notice a decrease, indicating it is

only water. Taste it. You’ll know.

That is all there is to it!

So far, you’ve just learned the basics. If all this is

totally unfamiliar, you might think it is too much to tackle. It isn’t. Even so,

you might make mistakes at first.

Think of yourself as a youngster watching your mother make a

three-layer chocolate cake with icing. She barely looks at the the cookbook and

it turns out great and tastes wonderful. Now you try it. You follow the recipe

exactly. You wind up with a real mess.

You are not expected to do everything right the first time.

You will blunder. But like your mother had to learn, to make it all look so

easy, you will learn and you will be doing these processes while barely looking

at the instructions.

![]()

A brief note on the quality of the images you’ve just seen. Kurt misplaced the

original file containing the photographs for this article so I was stuck with

using the newsprint copies taken right out of The Survivor. I am just beginning to understand all the things that can be done with Adobe’s Photo Shop imaging

software. Just as soon as I can, I’ll “touch up” all of the above

photos in an attempt to make them look a little better.—Cary

![]()